Una alumna me hace la siguiente pregunta

«Hemos visto que los núcleos exocéntricos son descartados por la teoría de la X-barra, pero ¿por qué existe la «endocentricidad»? ¿Por qué los sintagmas (de cualquier tipo) tienen núcleo? ¿Es por una restricción computacional? ¿Por una razón semántica? Quizás sea algo más general como la restricción cognitiva. Esa última opción es, por supuesto, muy tentativa. No sé si algo como la endocentricidad es relevante en otros dominios de la Naturaleza / Ciencia»

Esta ha sido mi respuesta

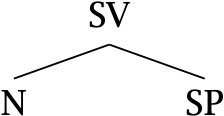

La principal razón para considerar que la endocentricidad es una de las propiedades esenciales de la teoría de la X-barra es la de evitar estructuras como las siguientes.

1 a. SV –> N SP

b. [SV [N destrucción] [SP de la ciudad]]

La endocentricidad de la teoría de la X-barra nos asegura que la «etiqueta» de la proyección máxima sea una proyección de alguno de los elementos contenidos en la proyección. A partir del ejemplo propuesto, podríamos encontrarnos con estructuras como (2a). No podemos decir que una estructura como (2a) es imposible, si aceptamos que T está subcategorizando un SV. Para excluir (2a), necesitamos decir que si T subcategoriza un SV, está también subcategorizado a su núcleo, V. En general, si una categoría X selecciona una proyección SY, está seleccionando también a Y, su núcleo. Sin la noción de endocentricidad, este modo de explicar las restricciones de subcategorización entre los elementos se vuelve imposible.

2 a. [ST Juan [T puede [SV destrucción de la ciudad]]]

b. T [__SV] (T subcategoriza un SV)

La endocentricidad no puede ser considerada un requisito del sistema Conceptual-Intencional. No es necesario un concepto como la endocentricidad para interpretar semánticamente las estructuras. El elemento «niños» en (3a) y el objeto sintáctico «ver niños» en (3b), a pesar de tener «etiquetas» o núcleos diferentes, reciben la misma interpretación. En ambos casos nos encontramos con predicados de individuos, es decir, funciones de individuos a valores de verdad si el individuo está en la extensión del predicado.

3 a. [SN [N niños]] – Interpretación semántica: la función f(x) que recibe el valor 1 si x es un niño, en caso contrario, f(x) recibe el valor 0

b. [SV [V ver] [SN niños]] – Interpretación semántica: la función f(x) que recibe el valor 1 si x ve niños, en caso contrario f(x) recibe el valor 0

Si establecemos una correspondencia entre rasgos categoriales e interpretación semántica, podemos definir qué objetos sintácticos se interpretan semánticamente de un modo u otro, independientemente de si los objetos sintácticos tienen un núcleo o una etiqueta. Por ejemplo, los elementos léxicos que contuvieran el rasgo categorial N, el rasgo categorial V o el rasgo categorial A serían, desde el punto de vista semántico, predicados, es decir, funciones de individuos a valores de verdad. Basta inspeccionar si el objeto sintáctico en (3a) tiene el rasgo categorial N o si el objeto sintáctico en (3b) tiene el rasgo categorial V para caracterizarlos como predicados semánticos, con independencia de cómo se hayan formado sintácticamente. Parece, pues, que la razón de la existencia de la endocentricidad no necesitar ser una «razón» semántica.

Podemos encontrar analogías a la endocentricidad en otros dominios. Según la física, el mundo es monista. Está constituido por combinaciones de elementos irreductibles. Mediante la unión de las partículas elementales que llamamos cuarks (*quark* en inglés) se forma todo el universo. Hay distintos tipos de cuarks, definidos por especificaciones diferentes de propiedades básicas o rasgos, que interactúan entre sí para formar partículas más grandes como fotones, electrones, protones, neutrones, átomos, moléculas,… hasta llegar a nosotros, los seres humanos. Pero la analogía se detiene ahí. No tiene sentido explicativo afirmar que el núcleo de un ser humano es un conjunto de cuarks. Los seres humanos no son una «proyección» de cuarks. Los sistemas complejos como nosotros, formados por la combinación de partículas más simples, pierden propiedades que sus constituyentes elementales tenían. También ganan otras que no existían en los elementos originales.

El mundo cuántico de los electrones y los átomos y el mundo físico de los objetos con los que interactuamos tienen propiedades complementamente diferentes a pesar de estar formados por los mismos elementos, los cuarks. Los SSVV o los SSNN que actúan sintácticamente no pierden las propiedades que les otorgan sus respectivos núcleos, sus elementos más simples, cuando forman elementos más complejos como ST/SFlex o SC. Cuando un SN y un SV se unen para formar una oración tampoco obtienen propiedades de las que sus núcleos carecieran. ¿Cómo es esto posible? Posiblemente, porque los principios constitutivos que llevan desde el cuark hasta el ser humano no obedecen la endocentricidad que reconocemos en los objetos sintácticos.

Parece que el requisito de endocentricidad es, por tanto, una restricción del sistema computacional. Se trataría de uno de los requisitos impuestos por la naturaleza misma de la Gramática Universal, el sistema interno que nos permite formar estructuras lingüísticas de carácter infinito y discreto. La endocentricidad sería un factor del primer tipo (Chomsky, 2005) en el diseño de la facultad de lenguaje. Sería una de las propiedades exclusivamente lingüísticas que definen el sistema. Desde este punto de vista, no tendría por qué tener correlatos en otros dominios.

Para saber más:

Chomsky, N. (2005). Three Factors in Language Design. Linguistic Inquiry, 36(1), 1-22.doi: 10.1162/0024389052993655.

Collins, C. (2002). Eliminating labels. En S. D. Epstein & T. D. Seely (Eds.), Derivation and explanation in the Minimalist Program. Malden, MA: Blackwell Pub.

Speas, M. (1990). Phrase structure in natural language (Studies in natural language and linguistic theory; v. 21). Dordrecht; Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7524-7636

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7524-7636